HodorCSE

Localization of software, while not trivial, is not a particularly novel problem. Where it gets more interesting is in resource-constrained systems, where your ability to display strings is limited by display resolution and memory limitations may make it difficult to include multiple localized copies of any given string in a single binary. All of this is then on top of the usual (admittedly slight in well-designed systems) difficulty in selecting a language at runtime and maintaining reasonably readable code.

This all comes to mind following discussion of providing translations of Doors CSE, a piece of software for the TI-84+ Color Silver Edition1 that falls squarely into the “embedded software” category. The simple approach (and the one taken in previous versions of Doors CS) to localizing it is just replacing the hard-coded strings and rebuilding.

As something of a joke, it was proposed to make additional “joke” translations, for languages such as Klingon or pirate. I proposed a Hodor translation, along the lines of the Hodor UI patch2 for Android. After making that suggestion, I decided to exercise my skills a bit and actually make one.

Hodor (Implementation)3

Since I don’t have access to the source code of Doors CSE, I had to modify the binary to rewrite the strings. Referring the to [file format guide][linkguide], we are aware that TI-8x applications are mostly Intel hex, with a short header. Additionally, I know that these applications are cryptographically signed which implies I will need to resign the application when I have made my changes.

Dumping contents

I installed the IntelHex module in a Python virtualenv to process the file into a format easier to modify, though I ended up not needing much capability from there. I simply used a hex editor to remove the header from the 8ck file (the first 0x4D bytes).

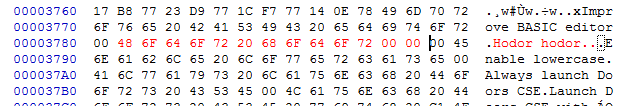

Simply trying to convert the 8ck payload to binary without further processing doesn’t work in this case, because Doors CSE is a multipage application. On these calculators Flash applications are split into 16-kilobyte pages which get swapped into the memory bank at 0x4000. Thus the logical address of the beginning of each page is 0x4000, and programs that are not aware of the special delimiters used in the TI format (to delimit pages) handle this poorly. The raw hex file (after removing the 8ck header) looks like this:

:020000020000FC

:20400000800F00007B578012010F8021088031018048446F6F727343534580908081020382

:2040200022090002008070C39D40C39A6DC3236FC30E70C3106EC3CA7DC3FD7DC3677EC370

:20404000A97EC3FF7EC35D40C35D40C33D78C34E78C36A78C37778C35D40C3A851C9C940F3

:2040600001634001067001C36D00CA7D00BC6E00024900097A00E17200487500985800BDF8

[snip]

:020000020001FB

:204000003A9987B7CA1940FE01CA3440FE02CAFB40FE03CA0541C3027221415D7E23666FAD

:20402000EF7D4721B98411AE84010900EDB0EFAA4AC302723A9B87B7CA4940FE01CA4340B9

:20404000C30272CD4F40C30272CDB540C30272EF67452100002275FE3EA03273FECD63405BLines 1 and 7 here are the TI-specific page markers, indicating the beginning

of pages 0 and 1, respectively. The lines following each of those contain

32 (20 hex) bytes of data starting at address 0x40000 (4000). I extracted

the data from each page out to its own file with a text editor, minus the

page delimiter. From there, I was able to use the hex2bin.py script provided

with the IntelHex module to create two binary files, one for each page.

Modifying strings

With two binary files, I was ready to modify some strings. The calculator’s

character set mostly coincides with ASCII, so I used the strings program

packaged with GNU binutils to examine the strings in the image.

$ strings page00.bin

HDoorsCSE

##6M#60>

oJ:T

Uo&

dQ:T

[snip]

xImprove BASIC editor

Display clock

Enable lowercase

Always launch Doors CSE

Launch Doors CSE with

PRGM]With some knowledge of the strings in there, it was reasonably short work to find them with a hex editor (in this case I used HxD) and replace them with variants on the string “Hodor”.

I also found that page 1 of the application contains no meaningful strings, so I ended up only needing to examine page 0. Some of the reported strings require care in modification, because they refer to system-invariant strings. For example, “OFFSCRPT” appears in there, which I know from experience is the magic name which may be given to an AppVar to make the calculator execute its contents when turned off. Thus I did not modify that string, in addition to a few others (names of authors, URLs, etc).

Repacking

I ran bin2hex.py to convert the modified page 0 binary back into hex, and

pasted the contents of that file back into the whole-app hex file (replacing

the original contents of page 0). From there, I had to re-sign the

binary.4 [WikiTI points out][wikiti] how easy that process is, so I

[installed rabbitsign][aur] and went on my merry way:

$ rabbitsign -g -r -o HodorCSE.8ck HodorCSE.hexTesting

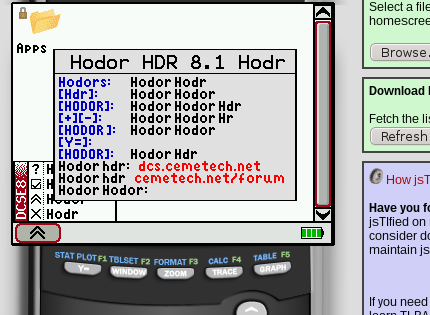

I loaded the app up in an emulator to give it a quick test, and was met by complete nonsense, as intended.

I’m providing the final modified 8ck here, for the amusement of my readers. I don’t suggest that anybody use it seriously, not for the least reason that I didn’t test it at all thoroughly to be sure I didn’t inadvertently break something.

Extending the concept

It’s relatively easy to extend this concept to the calculator’s OS as well (and in fact similar string replacements have been done before) with the OS signing keys in hand. I lack the inclination to do so, but surely somebody else would be able to do something fun with it using the process I outlined here.

That name sounds stupider every time I write it out. Henceforth, it’s just “the CSE.” ↩︎

The programmer of that one took is surprisingly far, such that all of the code that feasibly can be is also Hodor-filled. ↩︎

Hodor hodor hodor hodor. Hodor hodor hodor. [linkguide]: http://www.ticalc.org/archives/files/fileinfo/247/24750.html ↩︎

This signature doesn’t identify the author, as you might assume. Once upon a time TI provided the ability for application authors to pay some amount of money to get a signing key associated with them personally, but that system never saw wide use. Nowadays everybody signs their applications with the public “freeware” keys, just because the calculator requires that all apps be signed and the public keys must be stored on the calculator (of which the freeware keys are preinstalled on all of them). [wikiti]: http://wikiti.brandonw.net/index.php?title=84PCSE:OS:Applications#Signing_the_Application [aur]: https://aur.archlinux.org/packages/rabbitsign/ ↩︎