Reflecting on Breath of the Wild

I’ve been enjoying The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild recently, and reflected some on what makes it interesting to me from a non-gameplay perspective. This document is a version of those musings organized for publication, though perhaps less well organized than my usual writings- I am by no means a skilled critic, but spending longer in composing this would likely just delay its completion to little benefit.

Note that at the time of this writing I have not yet completed the game, but there are still some minor spoilers for the early portions of the game and general premise.

A bit of a callout to Metal Gear Solid 3, here.

I haven’t really played any Zelda games before Breath of the Wild. Once (long ago) I played a little bit of A Link to the Past but didn’t find it interesting (and was bad at it). Similarly, some time later I tried Ocarina of Time and failed to find anything compelling about it. Claiming that those games are simply not fun would be disingenuous, given both of them appear in multiple lists of “greatest video games ever” compiled by various parties. The correct question to answer here is then which of the differences between those earlier games and Breath of the Wild make the latter interesting to me, but the former not.

Having had extremely limited exposure to earlier Zelda games, I am in a poor position to comment on gameplay differences. In principle I appreciate the open design of Breath of the Wild that allows the player to go anywhere and do just about anything following the completion of a short tutorial section, but it seems to me that I have not been taking much advantage of that freedom. My general impression of the older Zelda style is that there is usually only one way to progress and that may be a frustrating factor that is not highly ranked in my mind however, whereas Breath of the Wild has given me as a player a sufficiently precise goal and the freedom to go after it at any time, but also hints as to things I may do to make success in that quest more probable.

It’s possible that merely offering more freedom to the player and applying contemporary popular game design principles (and resources) to the general Zelda formula is enough to capture the interest of the Present Me. Certainly when I tried the other above-described games they would have been relatively old so I may have been accustomed to games simply built with different style.

On the other hand, I have opinions about how Zelda has previously approached storytelling and how it does in Breath of the Wild which make for rather more interesting thoughts, so I will turn to those considerations instead.

The Big Bad

My general impression of the typical Zelda plot is “oh no stop the evil man from doing the evil thing.” As far as it goes, that’s fine but I find it uninteresting. Breath of the Wild takes a somewhat different approach to the general concept that I find much more compelling.

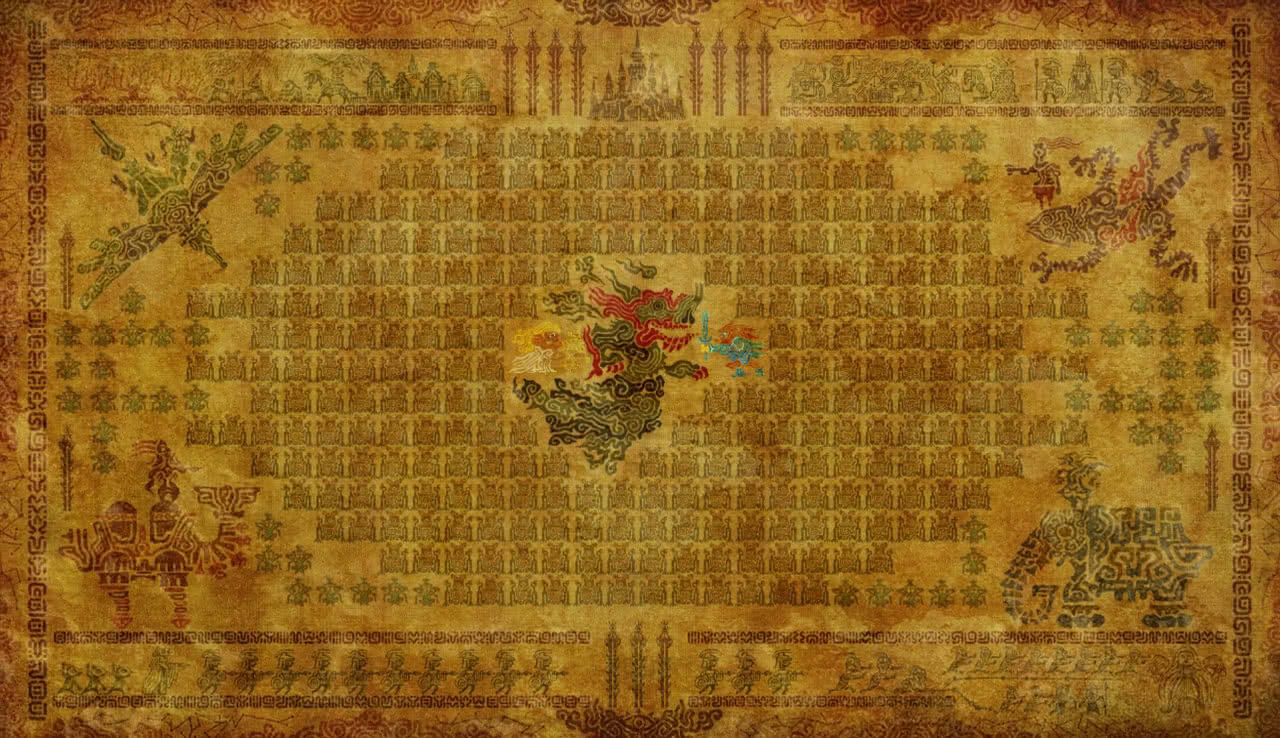

Elemental evil infests the seat of power.

Ganon, the usual Big Bad, is depicted as an elemental evil in Breath of the Wild, rather than some kind of dark wizard. If a mere dark wizard could be the source of an existential threat of the sort that requires a Great Hero (the player) to protect the world, it seems that there would be more frequent existential threats. Given the presentation suggesting that the player is a unique and noteworthy hero (for instance, collecting artifacts that are implied to be unique and offer powerful abilities to a chosen wielder), putting them in a world where the threat demanding heroism is as mundane as a dark wizard of some kind is rather unconvincing.

The ability of the player character to defeat this elemental evil is not (at least from the start) taken as self-evident, in comparison to how I see other Zelda games, which from the beginning seem to take it as given that the player character is destined to become a great hero and save the world.

A wild landscape with aspects of decaying grandeur.

Breath of the Wild starts with the player as the only sentient being in a wild landscape with traces of former glory, quickly introducing a guide sort of character who acts as a gently-guided tutorial before giving fuzzy backstory about how the player character is essentialy one in a long line of heroes. The details of this are revealed over hours of gameplay, largely leaving the player alone in a vast world scattered with suggestions of a long history.

I previously found the official canon for Zelda to be rather silly, because every new game is basically the same structurally (Link the hero must do hero things to assist/rescue Zelda the princess-heroine from the Big Bad). This has been justified as that they are these recurring characters over very long periods of time, but it struck me mostly as a convenient excuse for recycling characters that are well-liked.

A world with history

In Breath of the Wild the history of the world is used to good effect, including the recurring nature of the major characters. Lore-keeping NPCs allude to the distant past and what are effectively past incarnations of the main characters, while side characters are more defined by their roles so it is plausible to reuse them.

The elemental evil is eternally opposed by the guardian souls.

The world itself acts as a testament to the long history of the land, with ruined structures dotting the landscape (often large stone constructions that are impressive even as ruins) and even older structures (shrines) that serve as a kind of waypoints in what might otherwise be aimless wandering for the player. While the shrines are largely ignored by NPCs, they are not invisible- NPCs seem aware of their presence, but because they are not useful go largely ignored. If there is a weak point in this bit of world-building, the lack of interest or elaboration around shrines seems to be it- but this seems fair when these shrines are meant to be orders of magnitude older than any other relevant features of the landscape.

The art style might earn some credit for informing the feel of the world, but I don’t feel qualified to comment on that. I’ll leave comments on the art of the game to commentators better informed about art, leaving my thoughts at how it seems to be a good use of the limited computing power available to the game’s developers, recognizing that the Wii U and Switch are underpowered systems by the standards of other contemporary gaming platforms.

Characterization

I noted earlier that Breath of the Wild does not seem to take it as given that the player’s character is destined to become a great hero and save the world, but an alternate interpretation might be that the player already has hero credentials. It is shown early on that Link was some kind of royally appointed champion, and it is then implied that those selfsame credentials derive to some extent from Link being an embodiment of a spirit that protects the world through time immemorial.

Only the Chosen Hero can wield the Sword that Seals the Darkness!

Despite these heroic credentials, the player at the beginning of the game is effectively powerless, having been idle (unconscious) for a century, following a disastrous defeat at the hands of an encroaching Ganon.

Much of the characterization is done through flashbacks, which I find pretty effective. Putting this kind of backstory in-line might have been distracting and taken away from the feel of a desolate and ruined world, which makes for some of the most intriguing parts of the setting.

It is a bit unusual among games (those with this kind of budget available at least) that this one largely does without voice acting- most characters (the player included) “speak” in what amounts to grunts, except in flashbacks and with a few major characters who are fully voiced. This works well I find; they are not particularly wordy, and suggest some kind of connection between Link and the world’s past, making the player’s task something more resembling a quest to regain the glory of the land, rather than just preventing a cataclysm (which has already happened!).

I appreciate the gravitas of the voiced instances in general as appropriate to the events surrounding a kingdom under mortal threat. Despite that, there are welcome comedic and otherwise lighthearted instances that seem appropriate when considering that Link and Zelda are supposed to be relatively young. In particular, Zelda as a character does not come across to me as a nearly-omniscient plot device (“go here and do this, you must!”), but instead as a typical person thrust into a position of power as royalty doing what they feel is right in a difficult situation.

Zelda accepts a difficult role when the best efforts of the people have failed.

Other characters help the game illustrate that in the past Link is coming from, there were organized attempts to resist the impending doom embodied in Ganon. Compare this to my impression of other Zeldas, where if anybody else is aware of the existential hazard that must be defeated by the player they foolishly choose to put their trust in the abilities of the player who begins with no credentials to speak of.

The most guidance any person gives to the player regarding how best to achieve their ultimate goal of defeating the Great Evil hanging over the land amounts to general information, stating what happened in the past and suggesting what might be helpful. Not only does this support the feeling that nobody knows a magical secret that will defeat Ganon, but it also meshes nicely with the feeling that the player is responsible for restoring the former glory of the land (and themselves), leaving it up to the player what level of achievement is appropriate.

If desired, a sufficiently skilled player can go directly from the game’s introduction to defeating the Big Bad, in some fashion asserting that there is nothing that need be reclaimed.

Concluding

With a largely ruined and wild world in the grip of an elemental evil, Breath of the Wild suggests that there is a long and glorious forgotten history to be rediscovered and reclaimed. Whereas the feeling I get from the narrative setup of other Zelda games is “become a hero and save the land!”, this one is closer to “reclaim the forgotten glory of the land by rediscovering your own heroic nature.” Less a story of self-actualization, the player is fighting the universe itself to build a better world for themselves and every other character in it- but they are granted great freedom to decide what must be done and how.

Nice framing of a highly visible goal.

Recognizing my preferences in fiction, it is hardly surprising that I find Breath of the Wild’s approach to storytelling compelling. For instance, I quite enjoy the works of Alastair Reynolds, which often have themes relating to inhumanly long timescales and the inability of humans to comprehend all relevant aspects. Taken slightly differently, I greatly appreciate Lovecraftian horror with its bleak outlook and Breath of the Wild hits some similar notes (albeit in a much more positive fashion).

So, yeah. I like Breath of the Wild and really appreciate how it diverges from other Zelda games in presentation (though I lack the perspective to objectively judge how much it actually differs!). Even if you, dear reader, have found other Zelda iterations uninteresting, this one might be worth looking at.

At this point I’m just appreciating the scenery.