Doing what Nintendon't with the Hero's Path

The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom is an excellent video game, which I’ve only recently (about three weeks ago, at the time of writing) played to a satisfactory conclusion; it took me around 90 hours of gameplay over nearly 150 real-time days to reach that point, representing a pretty significant amount of my free time. I previously wrote about what I liked about Breath of the Wild, its predecessor and although I found a few aspects of Tears of the Kingdom’s (henceforth “TOTK”) plot less compelling than Breath of the Wild (“BOTW”), the scale of the newer game and its overall presentation left me extremely satisfied on its completion. Between them, I’d say these most recent Zelda games are strong contenders for the title of “best videogame” with no qualifiers.

Other people have written much more eloquently about what makes TOTK such an exquisite game, so I won’t spend more words on that. My reason for writing is a thought I had on completion of the game relating the Hero’s Path feature and what I might be able to do with its underlying data beyond the scope of the game’s features.

Hero’s Path

The Hero’s Path is a feature of both BOTW and TOTK that records the player’s position in the game world at intervals and allows it to be viewed on the map, recording up to around 250 hours of gameplay. This is often a convenient feature during gameplay because it becomes easier to explore the world by being able to see areas that have or have not been visited, and especially in being able to play it back (animating the player position over the world) can be a neat tool for reminiscence.1

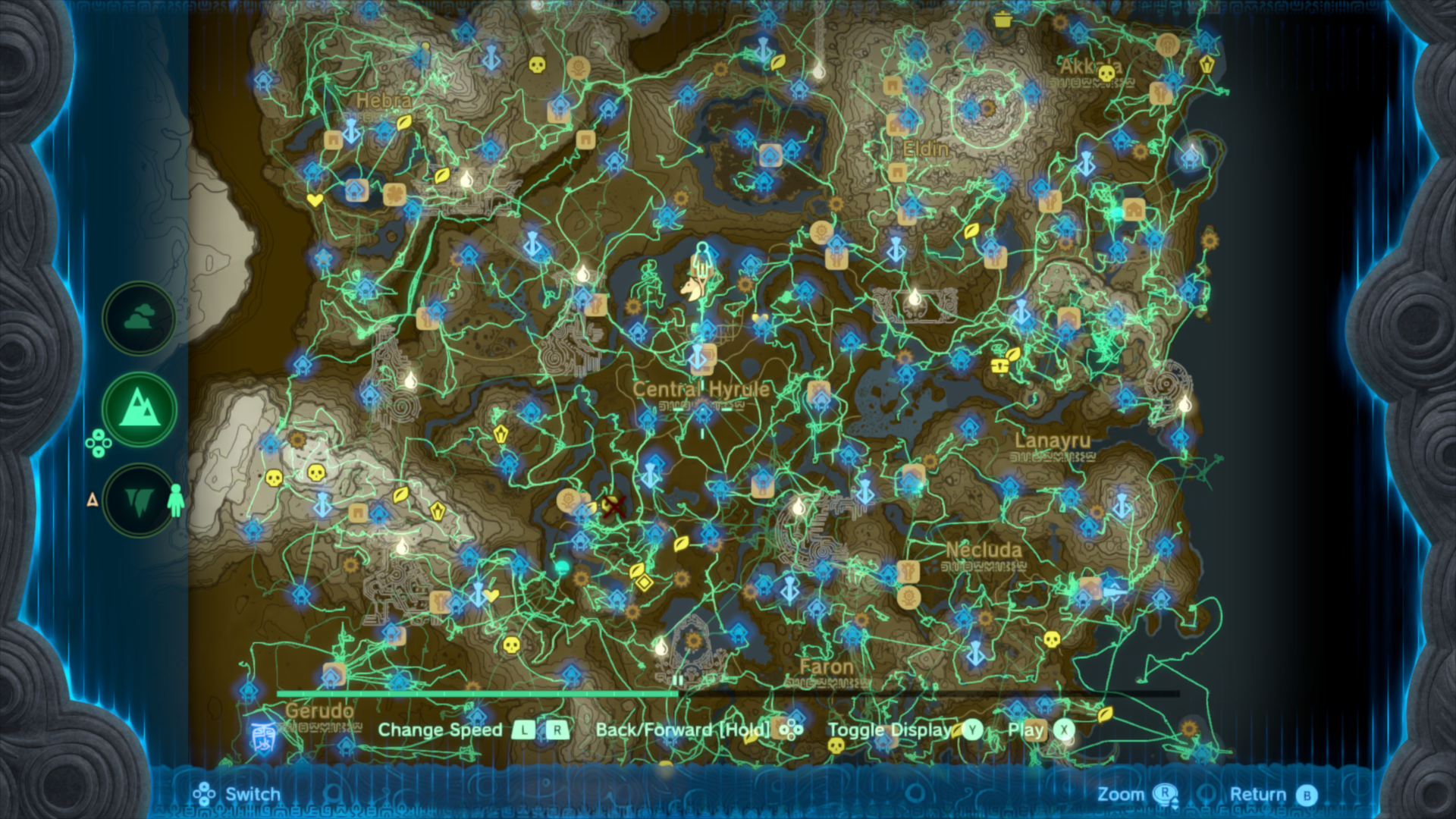

The Hero’s Path displayed on my TOTK save’s map at the time I completed the game.

Since the Hero’s Path captures such a large amount of gameplay, it seems like it may be interesting to mine for data or simply view in different ways. With those concepts in mind, I set out to learn how it’s stored in the game’s save data in order to extract the data and do new things with it.

File format investigation

To even begin investigating the data format, I first needed to get some save data. Nintendo would seemingly rather you never have access to the actual data stored on a Switch and only be able to make copies on their servers to back up your saves. Fortunately for me, independent programmers building homebrew software have been at it for years now and I have a Switch that’s vulnerable to CVE-2018-6242 ("Fusée Gelée"), so it is fairly straightforward to load up JKSV on my game system and make a copy of my save game for TOTK.

First look

With data in hand, the first thing to do is look at the files that make up the save. It turns out to be structured with a few independent slots and some additional data that seems shared across every slot:

| Directory | File(s) | Size | |

|---|---|---|---|

| album | 000_Photo.jpg | 63 KB | |

| 000_Thumb.jpg | 8 KB | ||

| 001_Photo.jpg | 63 KB | ||

| Pattern continues with increasing numbers. Some photos have accompanying .figi files (039_FigureInfo.figi). | |||

| DeathMountainHatago.jpg | 61 KB | ||

| Additional "Hatago" images follow, with names seemingly corresponding to locations in the game world. | |||

| LinkHousePicture_1.jpg | 64 KB | ||

| picturebook | Animal_Bear_A_Detail.jpg | 62 KB | |

| Animal_Bear_A_Icon.jpg | 6.5 KB | ||

| Many other detail and icon pairs follow, in categories like Animal, Enemy, Item and Weapon. | |||

| slot_00 | caption.sav | 11 KB | |

| direct_file_save_related.sav | 1 KB | ||

| footprint.sav | 600 KB | ||

| progress.sav | 2.2 MB | ||

| slot_01 | same files as slot_00 | ||

| slot_0* | pattern continues up to slot_05 | ||

| storage | CacheStorageKey.dat | 9 bytes | |

At only 9 bytes, it doesn’t seem like the CacheStorageKey file contains anything interesting; I haven’t investigated it at all. The other directories look more interesting.

album

The album directory is pretty clearly the in-game album, which allows the player to take photos at almost any time during gameplay; this can be identified easily simply by looking at the JPEG files. A full-resolution image (1280x720) is stored alongside a thumbnail (256x144).

000_Photo.jpg in my save is recognizable as one of the default photos created when starting a new game, meant to be a photo taken by Princess Zelda during the prologue.

Not every photo has a corresponding FigureInfo file, but I infer that the .figi files contain information about the photo’s subject and its pose at the time the photo was taken. This information must be used for the ability to make monster sculptures by speaking with Kilton in Tarrey Town, since in the game context it converts a photo of a monster back into a 3D model in the same pose. Regenerating that information only from an image would be exceptionally difficult, so I expect the .figi files contain the relevant information captured at the same time as the photo.

Monster sculptures arrayed in their designated space at Tarrey Town. From this angle it’s not obvious, but some of the poses are a bit awkward which demonstrates that each monster probably does not have curated poses and they instead take the same pose as they had at the time an image was captured.

The “Hatago” and “LinkHouse” images are presumably the images which can be seen in each stable2 (filled by completing the various “A Picture for the name Stable” side quests) and in certain rooms available for the player-built “dream home”, both of which accept pictures taken with the in-game camera.

picturebook

Similar to the album, the picturebook directory appears to be the contents of the Hyrule Compendium, where after a

photo is taken of an object of a particular type a few sentences of additional information can be viewed at any time

alongside the original photo of that object. Cropped versions of the photos are visible when browsing the Compendium in

the game, so it’s logical that each object has Detail and Icon images.

A sample compendium entry for one of the several hundred items and objects that can be viewed therein. The image at the center of the screen is used with reduced resolution as the icon, and the detailed image fills the entire screen behind the rest of the UI.

As with the album, the full image for each entry is 1280x720 pixels but the icons are slightly smaller; only 168x168 pixels.

slots

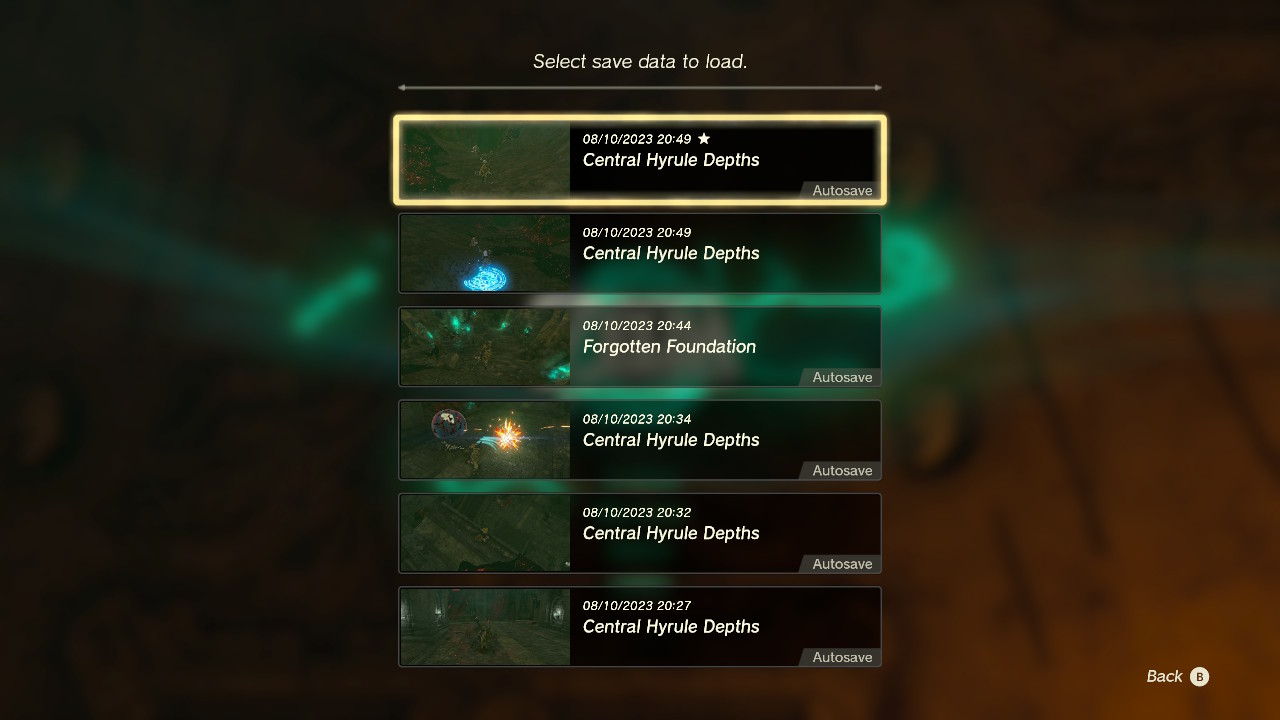

Having looked at everything else, the slot_ directories look like the real meat of a save. With up to six of them present, each corresponds to the slots available to a game from where one is always the last manual save (made by selecting the Save option in menus) whereas the other five are autosaves that the game makes periodically.

A sample of six save slots in the menu to load a game. Note that all but one are marked as autosaves.

The assignment of saves to slots doesn’t follow any obvious pattern, but it seems like the slots are probably allocated round-robin when autosaving (cycling from 0 to 5 and back to 0) while skipping the slot that has a manual save in it. Marc Robledo suggests examining caption.sav to get the meta-information for each slot which should correspond to the information shown in the loading menu.

Saving some work for me, Marc’s savegame editor understands a lot of structure of the game’s save data and its source code is available so it can act as a form of documentation. That tool only supports loading caption.sav (the aforementioned metadata) and progress.sav which seems like it contains all of the core gameplay state like the player’s location and owned items.

There is no indication that either of these files contains the Hero’s Path data, so to continue the investigation that I wanted to do, footprint.sav was the clear choice; certainly it’s reasonable to assume that the game developers would have referred to it as a collection of footprints indicating where the player has been. direct_file_save_related.sav is left with an unknown purpose, but its small size probably indicates that its contents are uninteresting to me.

footprint.sav

The first thing I looked for regarding footprint.sav was whether anybody else had already documented the format. As expected (because I had also looked to see if a tool along the lines of what I wanted to create existed before I started), I didn’t find any useful documentation on its format. I did find a question relating to the TOTK save editor where the author claimed that footprint.sav contained the Hero’s Path data but further stated that nobody had documented its format.

Recognizing that TOTK is built in very similar ways to BOTW, I also looked to

see if anybody had documented the data format used for the Hero’s Path in Breath

of the Wild- there’s a chance they would use exactly the same format if the

developers didn’t feel any need to change it between the two games. In this

respect I found that Kevin Jensen had shared an informal

specification, though it wasn’t immediately useful. It

turns out that BOTW creates multiple trackblock.sav files each of which covers

around 8 hours of gameplay. Since TOTK clearly doesn’t split the footprint files

in this way, it’s unlikely to have the same overall structure.

Diffing

With nowhere else to start, I chose to begin by seeing how each of the save slots differed in their contents. Starting with the idea that it would be useful to explore how a tool like xdelta3 would express the differences between two of the slots which probably represented a short time difference. Using an optimized tool turned out to be difficult because I wanted something that I could interact with from Python (which I was planning to do any required programming work in) and I failed to get any of the libraries I found for binary diffing in Python to work.

Fortunately, a Stack Overflow commentor

noted that Python’s built-in difflib can also be used for binary diffs.

Arbitrarily choosing to start with slots 0 and 1, I printed out how difflib

thinks the footprint files differed:

| |

get_opcodes took a long time to run (several minutes or more), but emitted

only four opcodes:

[('equal', 0, 76, 0, 76),

('replace', 76, 77, 76, 77),

('equal', 77, 272796, 77, 272796),

('replace', 272796, 614760, 272796, 614760)]To make sense of this output, I the get_opcodes documentation says that these

constitute a set of instructions to convert the a input into b. They’re the

same (equal) for the first 76 bytes, and from bytes 77 through 272796, then

seemingly differ from there to the end of the file.

Since I didn’t know exactly how these two slots correlated with each other (which one is newer, in particular), I did the same thing to compare slots 1 and 2 rather than 0 and 1:

[('equal', 0, 76, 0, 76),

('replace', 76, 77, 76, 77),

('equal', 77, 272868, 77, 272868),

('replace', 272868, 614760, 272868, 614760)]Based on the lengths of the equal segments, it looks like slot 1 has 272868 -

272796 = 72 bytes more in it than slot 0.

With a little bit more of an idea of what happens to a save over time (it looks like data simply gets appended), I then visually inspected the first 80 bytes of each slot’s footprint file to see both what the overall structure looks like and investigate what changes at offsets 76 and 77 which changed in each pair of slots that I compared:

>>> for slot in range(0, 6):

... name = f'slot_{slot:02}'

... with open(f'{name}/footprint.sav', 'rb') as f:

... print(name, f.read(80).hex(sep=' '))

slot_00 04 03 02 01 f4 e0 47 00 58 01 00 00 00 00 00 00

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 59 68 a0 c5 01 00 00 00

6b 6f dc 37 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 00 00

00 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 43 c2 e8 08 0c 0a 01 00

slot_01 ...

00 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 43 c2 e8 08 1e 0a 01 00

slot_02 ...

00 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 43 c2 e8 08 69 0a 01 00

slot_03 ...

00 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 43 c2 e8 08 c7 0a 01 00

slot_04 ...

00 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 43 c2 e8 08 e5 09 01 00

slot_05 ...

00 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 43 c2 e8 08 90 0a 01 00Not paying much attention to the other bytes, it looked like the bytes at offsets 76 and 77 were part of some kind of count that increases over time. I guessed that it could be a multibyte integer and might be a number indicating how many data points are stored, and found that these values look like an incrementing counter if treated as little-endian:

- 0x09e5

- 0x0a90

- 0x0a0c

- 0x0a1e

- 0x0a69

- 0x0ac7

Since I didn’t think this would be a 16-bit integer, I also guessed that it would be 32 bits. That would include the following bytes with value 1 and 0, yielding values like 0x000109e5.

Further noting that it looked like slot 1 had 72 bytes more of data than slot 0, the difference of the two slots’ counter values was 0x010a1e - 0x010a0c = 18. 72 bytes divided by 18 is 4, which could indicate that this counter measures a quantity of 32-bit data points. Recalling the documentation for BOTW’s trackblock data, it stored a single 32-bit datum for each player location so this seemed like a solid guess.

Trying to also understand what changes where data gets added to a slot, I printed out the data from slots 0 and 1 beginning shortly before they differ and going to where slot 1 appeared to end. This turned out to be unremarkable: the longer slot had nonzero values past offset 272796 (where the shorter one ended) while the shorter slot’s data was all zero. This supported the idea that new data simply gets appended to the end of a file and a counter increments to track where the data ends.

slot_00 b0 39 78 25 30 3d 98 25 30 3f 78 25 f0 3e 48 25

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

slot_01 b0 39 78 25 30 3d 98 25 30 3f 78 25 f0 3e 48 25

30 41 48 27 70 41 58 27 30 44 28 27 f0 44 48 27

70 44 08 27 f0 44 48 27 70 3f 88 26 30 38 d8 26

70 35 d8 26 b0 35 e8 26 f0 34 38 27 30 3c 28 27

b0 3e c8 25 30 45 58 27 70 47 b8 26 70 45 48 27

f0 43 f8 26 b0 3e 38 28With this initial look, I had enough to start trying to make sense of individual points: the 32-bit little-endian value at file offset 76 indicates how many 32-bit values are present, beginning at offset 364. Presumably the remaining 360 bytes of header are useful in some way, but are uninteresting at this time.

Point data

With an idea that the points were simply a list of 32-bit values, I then needed to start looking for patterns in each value to understand their meaning. Glancing at the values from slot 1 I had printed out to compare with slot 0, I noticed a few values that looked like they differed only slightly and were in sequence. The bytes and a possible little-endian interpretation of each:

| Bytes | Little-endian value |

|---|---|

f0 44 48 27 | 0x274844f0 |

70 44 08 27 | 0x27084470 |

f0 44 48 27 | 0x274844f0 |

70 3f 88 26 | 0x26883f70 |

The f0 44 value appears twice here, possibly indicating two points in the track at the same location or that each

value is actually 64 bits wide and the intervening values capture some difference. The second value (70 44 ..) also

has a very short Hamming distance from the first and third, differing

in only two bits: f0 to 70 clears bit 7 and 48 to 08 clears bit 6 of the corresponding byte. The small Hamming

distance suggests to me that each point probably is 32 bits of data, and any two points will tend to have small

differences because the player won’t move very far between each point.

Being pretty confident that each point is stored in 4 bytes, I then needed to look for actual map coordinates in each point. Based on the data length for each slot and being able to tell that older saves will have shorter data length, I determined that in this instance my slot_02 save was the second-oldest entry in the game loading menu. I loaded that game and had a look at the map:

The map state as seen when loading my save in slot 1. Note that the current X, Y and Z coordinates are displayed in the lower right.

Also looking at the Hero’s Path in that save slot, the most recent movements were all in a fairly small area near the current location (-248, 648, -1225).

I know that at the time of this save I had been moving downward in a small area, so the somewhat circular pattern immediately south of the current location here is the most recent movements. Note that the marker for the most recent location in the path (the green person icon) is not at exactly the same location as the yellow triangle marking the current player location, though they are very close together.

Knowing that the recent footprint points stored in this save slot should be near to the position (-248, 648, -1225), my next step was to search for bit patterns in each 32-bit value that are similar to each component of those coordinates. I simplified this search somewhat by assuming that the game would store only a layer indicator (Sky, Surface, or Depths) rather than a full Z-coordinate for each point for two reasons:

- Jensen’s documentation says BOTW used 13-bit sign-and-magnitude representation for X and Y coordinates, which wouldn’t fit in 32 bits if it were extended to store a similar Z coordinate.

- Only an indication of which layer is relevant would be needed to display the path in the game, since TOTK only needs to dim parts of the track which are on layers not currently being viewed. In the image above, the dimmer portions of the track are from player movement on the surface or in the sky because the map is currently showing the depths and there is no way to visualize historical elevation changes.

Pattern-matching

Taking the last 32-bit value stored in this slot’s point data, the bytes are f0 3e 48 25. Assuming TOTK still used a 12-bit sign-and-magnitude format for X and Y coordinates like BOTW did, I started looking for bit patterns similar to the X coordinate; 249 (000011111001), and the Y coordinate; 601 (001001011001).

Not knowing whether each point should be interpreted as a little- or big-endian value, I started with big-endian and laid the bits out in a graphical way that should make it easier to see patterns and keeping in mind that the value in this point is probably not exactly the same as the coordinates that I know.

| Big-endian | 0xf0 | 0x3e | 0x48 | 0x25 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| X (249) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Y (601)? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the big-endian interpretation we see an exact match for the X coordinate, but none for the Y.

| Little-endian | 0x25 | 0x48 | 0x3e | 0xf0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| X (249) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Y (601) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

Little-endian seems better; these 12-bit fields from bits 20-32 and 6-18 have values 251 and 596 which are very close to the known X and Y coordinates (offset by 2 and -5 units, respectively).

I next attempted the same interpretation an another slot that had player coordinates (-248, 648) and bytes

b0 3e 38 28 to verify that it looked reasonable:

| Little-endian | 0x28 | 0x38 | 0x3e | 0xb0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| X (248) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Y (648) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||

The Hamming distances in this instance are somewhat larger, but the differences in the supposed numbers are similar; it represents a shift of only (2, 5) units from the known player position.

With reasonable confidence in this basic layout of bits, I generated some more samples for myself by loading up a game and taking known movements in order to try to identify the sign of each coordinate and validate that they seem to be 12-bit values:

- Start at position (-155, 1155)

- Teleport to (222, 1085)

- Teleport to (4632, -3712) and stay there for a while

By inspecting the values written into the Hero’s Path after doing this, I found the following 4-byte values:

- 0x483826ec

- 0x43d83788

- 0x43d8378c

- 0xe8048608, repeated multiple times

I put these four values into the same visual form to inspect them:

| Bit number | 31 | 20 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0x483826ec | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Y = 1155 | 1 | 0 | X = -155 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0x43d83788 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Y = 1085 | 1 | 0 | X = 222 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0x43d8378c | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Y = 1085 | 1 | 0 | X = 222 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0xe8048608 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Y = -3712 | 0 | 1 | X = 4632 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

For the second and all subsequent values, I notice that bit 5 is cleared. Since only the first point has a negative X coordinate, I assume that bit 5 is set to negate the X coordinate; it is the sign bit for that value. Similarly, bit 19 changes from 1 to 0 when the Y coordinate becomes negative so that’s probably the sign of the Y coordinate although it’s odd that its meaning seems reversed from the X coordinate sign (being set to indicate a positive coordinate).

Only the first and third values have bit 2 set, but it’s also interesting that the point (222, 1085) appears twice (the second and third values) where the second appearance differs only in setting bit 2. The version of this data from BOTW seems to use one bit to indicate when the player teleports away from a location, which is probably what bit 2 is indicating; it’s a discontinuity in the track, where the next point shouldn’t be connected to this one with a line.

In the last point, the value of the 12-bit field for X coordinate is wrong, but making it 13 bits by including bit 18 as its most-significant bit yields the correct value: the X coordinate is actually 13 bits (plus sign), not 12!

In summary, the current theorized structure is:

- Bits 20 through 31 are the Y coordinate.

- Bit 19 is cleared if the Y coordinate is negative, or set if positive.

- Bits 6 though 18 are the X coordinate.

- Bit 5 is set if the X coordinate is negative, or clear if positive.

- Bit s it set at the beginning of a path discontinuity such as when the player teleports.

There are only 4 bits left with unknown meaning, assuming this is all correct.

Layer indication

As noted earlier, I believed these values would store only an indication of which layer of the world the player was on rather than a whole Z coordinate. Since after looking at the X and Y coordinates in more detail there are only four unknown bits which aren’t even all contiguous, this seemed like a correct assumption.

Given there are three layers, I guessed a two-bit field would be used to store the layer and the fourth value for that field would either be unused or have special meaning. To investigate where that might be and whether such an assumption was correct, I looked at the same six points again (the two depths points from initial pattern matching and four from extended experiments) while noting what layer they corresponded to:

| Layer | Value | Y coordinate | X coordinate | Unknown bits | Discontinuity | Unknown bits | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depths | 0x25483ef0 | 601 | -249 | 1 | 0 | No | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Depths | 0x28383eb0 | 633 | -250 | 1 | 0 | No | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Surface | 0x483826ec | 1155 | -155 | 0 | 1 | Yes | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Surface | 0x43d83788 | 1085 | 222 | 0 | 1 | No | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Surface | 0x43d8378c | 1085 | 222 | 0 | 1 | Yes | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Surface | 0xe8048608 | -3712 | 4632 | 0 | 1 | No | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Since the value of bits 3 and 4 changes from 2 to 1 when moving from the Depths to Surface, it’s a safe guess that those two bits indicate which layer a given point is on.

To determine

what value corresponds to the Sky, I then loaded a save and travelled into the sky, walked around

some and saved the game. Inspecting the resulting data however, I didn’t see any of the expected

points! There were only two more recorded locations, and both were near the last position before

I went into the sky. By walking around for a bit longer and saving again, I was able to get the

expected points to appear in the footprints file: it seems the game buffers footprints for

a time before writing them to footprint.sav, so by walking around for a bit more time

I caused it to buffer enough that the points I expected to see eventually got saved.

Looking at the points once I eventually got them, it seems the value 0 for bits 3-4 indicates the player is in the sky:

| Layer | Value | Y coordinate | X coordinate | Layer value | Discontinuity | Unknown bits | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sky | 0x67405dc0 | -1652 | 375 | 0 | 0 | No | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sky | 0x67105ac0 | -1649 | 363 | 0 | 0 | No | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

This leaves it unknown what layer 3 might refer to. In BOTW one of the bits is

described as indicating whether a point is “MainField or Dungeon / AocField”, but

it doesn’t seem like that’s a meaningful distinction in TOTK. For one, the dungeons

in the newer game are properly within the game world rather than behaving more like

pocket universes as they do in Breath of the Wild, where each of the dungeons fills

a space in the world but are larger inside than the space they fill and the

player is prevented from getting too near to them on the overworld. Second,

AocField appears to be an internal term referring to the completely separate

world containing the Trial of the Sword

in BOTW- TOTK has no equivalent; again, everything occurs in real space on the

overworld in the newer game. For lack of any sensible options, I’ve assumed that the

value 3 is unused for this field.

Before going on, I’ll summarize my understanding of the fields again:

| Bit number | 31 | … | 20 | 19 | 18 | … | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meaning | Y-coordinate magnitude | Y-coordinate sign (negative when clear) | X-coordinate magnitude | X coordinate sign (negative when set) |

| Set for discontinuity (warping away from this location) | Unknown | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The final mystery bits

With a good understanding of nearly every bit of data, to decode the remaining two unknown data bits I chose to mine a save for any points that set either of them (because every sample I’ve looked at so far has both bits clear).

I wrote a little bit of code to iterate through a footprint.sav file and print out

every point (binary and hex values) that set bit 0 or 1, alongside its location in the

file and the coordinates represented, yielding the following list:

01001100010000000111010111000010 0x4c4075c2 47 ( 471,-1220)

00110111111100000110011011000010 0x37f066c2 86 ( 411, -895)

01011101111100000000011011000010 0x5df006c2 299 ( 27,-1503)

01101011000000001000101100000010 0x6b008b02 661 ( 556,-1712)

01010110101100001100000111000010 0x56b0c1c2 737 ( 775,-1387)

01001010011000001011100000000010 0x4a60b802 918 ( 736,-1190)

01001101111000001011101111000010 0x4de0bbc2 934 ( 751,-1246)

01001110000000001011001100000010 0x4e00b302 956 ( 716,-1248)

01001101110000001011110111000010 0x4dc0bdc2 982 ( 759,-1244)

01101001100100000110101110000010 0x69906b82 1040 ( 430,-1689)

01100011110000000110001001000010 0x63c06242 1069 ( 393,-1596)

01100100111100000100100010000010 0x64f04882 1178 ( 290,-1615)

01100001001000000111001000000010 0x61207202 1188 ( 456,-1554)

00110000111110000101010110101010 0x30f855aa 1575 ( -342, 783)

00110001001110000101010011101010 0x313854ea 1579 ( -339, 787)

01000001011000001011001001101010 0x4160b26a 2598 ( -713,-1046)

01100000000100100110000011101010 0x601260ea 2723 (-2435,-1537)

01001010011100011111011001101010 0x4a71f66a 2729 (-2009,-1191)

01001010101000011111010010101010 0x4aa1f4aa 2734 (-2002,-1194)

01000101101000011111100001101010 0x45a1f86a 2776 (-2017,-1114)

10011010100000110000100001101010 0x9a83086a 2964 (-3105,-2472)

10100101111100110101111111101010 0xa5f35fea 3071 (-3455,-2655)

11000100100000111111001111101010 0xc483f3ea 3163 (-4047,-3144)

11001111001101000101100001101010 0xcf34586a 3224 (-4449,-3315)

11000001011000111110111100101010 0xc163ef2a 3566 (-4028,-3094)

11010010010101000011101011101010 0xd2543aea 3692 (-4331,-3365)

11011111101001000111011000101010 0xdfa4762a 3741 (-4568,-3578)

11100110000001000111101101101010 0xe6047b6a 3764 (-4589,-3680)

11100110001001000111110111101010 0xe6247dea 3771 (-4599,-3682)

11011111110001000110011010101010 0xdfc466aa 4240 (-4506,-3580)

11100001101101000110100101101010 0xe1b4696a 4367 (-4517,-3611)

11100001101101000110011000101010 0xe1b4662a 4413 (-4504,-3611)

11011111001001000110101110101010 0xdf246baa 4442 (-4526,-3570)

11100010111001000110111001101010 0xe2e46e6a 4457 (-4537,-3630)

01100010010110101101110010101010 0x625adcaa 4850 (-2930, 1573)

00111000101110100011111101100010 0x38ba3f62 5987 (-2301, 907)

01000100101010101001010001110010 0x44aa9472 6084 (-2641, 1098)

00000100110100101010100011110010 0x04d2a8f2 6279 (-2723, -77)

00000001100100101010100010110010 0x0192a8b2 6283 (-2722, -25)

00000110011100101010100011110010 0x0672a8f2 6297 (-2723, -103)

00000011010100101010000110110010 0x0352a1b2 6316 (-2694, -53)

01110000100100110000011111101010 0x709307ea 6632 (-3103,-1801)

01111011010010000010100011000010 0x7b4828c2 11255 ( 163, 1972)

11001101001000010101010101000010 0xcd215542 15872 ( 1365,-3282)

01110001111110101111110101001010 0x71fafd4a 18074 ( 3061, 1823)

01101111011000100100101110000010 0x6f624b82 27029 ( 2350,-1782)At a glance it’s easy to see that in this save bit 0 is never set so it might be unused. Bit 1 is set somewhat unpredictably, and not very often. I found the values between offset 3741 and 4457 interesting because they had fairly high density (with bit 1 being set with fairly high frequency given the number of points) and are all fairly close together, so I pulled up the map and went looking for what was in that area of the map.

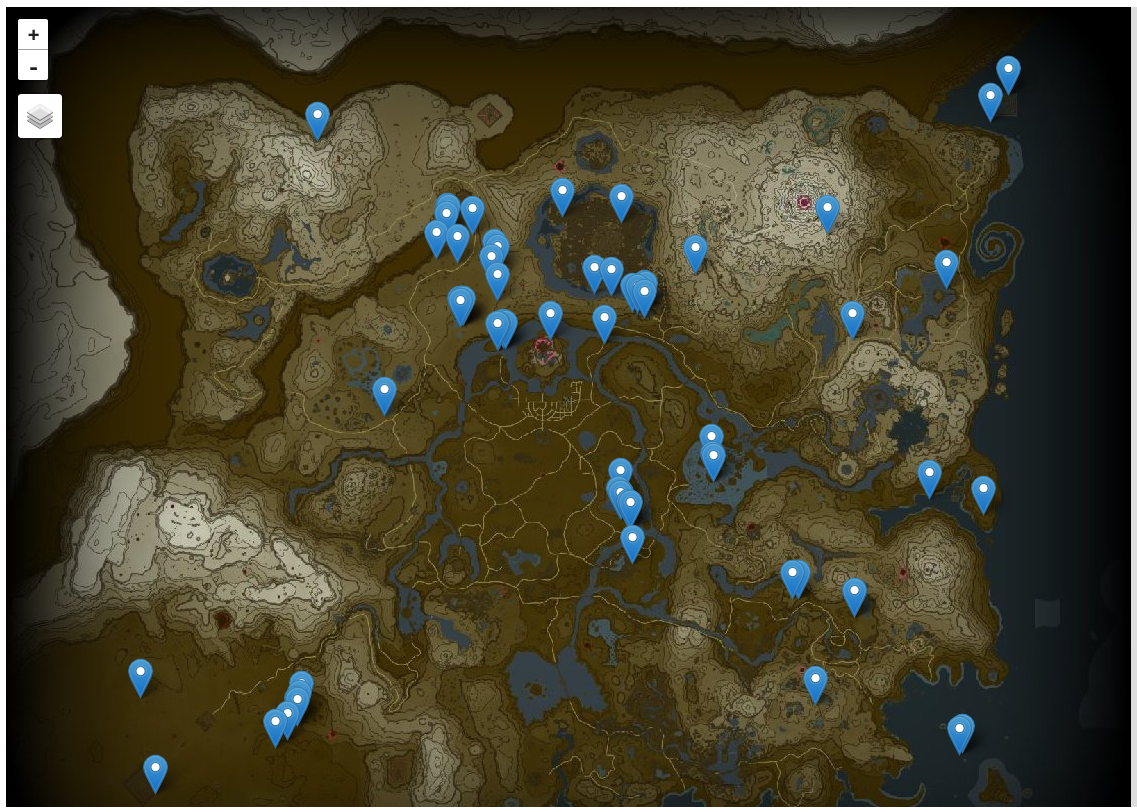

The area around (-4500, -3500) on the Surface is in and around the Lightning Temple (indicated by the larger blue icon) at the far Southwest corner of the world inside the Gerudo Desert.

I thought this bit could indicate when the player is inside a dungeon, but that seemed unlikely because the Hero’s Path is recorded normally when inside dungeons and there are still gaps between the points with it set. Perhaps it instead indicates where the player died, as one of the flags in BOTW did?

The game conveniently displays an icon on the map to mark the last place the player died, and in this case I found it was near (2350, -1782) in the Sky: exactly the coordinates of the last point I found that has bit 1 set! These coordinates are the entrance to a shrine, and I found that a number of the points surrounding this one in the file (around point 27029) are exactly the same except for bit 1. I suppose that this period of the track represents time spent inside this shrine (since shrines do behave like pocket universes by being much larger within than without), so the point at index 27029 is a time when the player died inside this shrine.

Complete data format

Having located no points that set bit 0, I was confident that it was either unused or

mostly unimportant so the following table summarizes the meanings of each field.

The values are 32-bit little-endian integers beginning at byte offset 364 in the

footprint.sav file, with the 32-bit little-endian integer at byte offset 76

indicating how many points are present.

| Bit number | 31 | … | 20 | 19 | 18 | … | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meaning | Y-coordinate magnitude | Y-coordinate sign (negative when clear) | X-coordinate magnitude | X coordinate sign (negative when set) |

| Set for discontinuity (warping away from this location) | Set for player death at this location (a different kind of discontinuity) | Unused? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

To experiment with the tracks in my save game, I also developed some Python code that

can load footprint.sav and collect the points, leaving them in a convenient format

to inspect.

| |

This can be used for quick inspection of data or as a building block for additional data analysis, for instance to show the locations of every death in a save:

| |

Running this on my save reveals that I died 67 times before completing the game, and shows the locations:

Found 67 deaths

Sky( 285,-1622) D

Sky( 473,-1598) D

Sky( 690,-1429) D

Sky( 748,-1416) D

Sky( 824,-1457) D

Sky( 833,-1451) D

Sky( 820,-1364) D

Sur( 392,-1087) D

Sur( 649, 873) D

Sur( 651, 873) D

...Mapping the path

Having figured out the data format to my satisfaction, I needed to be able to visualize the data to really be satisfied with the results. Fortunately, others had already done much of the work in making map data available in a way that I can reuse it easily. A person going by the handle Slluxx published a browser-based game map several days before the official release date of Tears of the Kingdom, which was later superceded by a very similar map on the Zelda Dungeon web site.

The Zelda Dungeon (ZD) map is more complete at this point, so I wanted to use it as a reference- fortunately its source code is available on GitHub even though I had to guess that its source was available and where rather than having it easily-discovered from the map on its own. I found by inspecting the sources that the ZD map uses the Leaflet library to display maps in the browser and that the tiles3 making up the map exist in their repository on GitHub.

Since I had been doing my investigation in a Jupyter notebook,

it was convenient that the ipyleaflet

library allows Leaflet maps to be embedded in a notebook. I was able to write a little bit

of code to display a zoomable map of Hyrule with only a little bit of reading documentation

and looking at the tile images in the ZD repository (which I found only provide zoom levels

0 through 6 and use an unusual tile size of 564 pixels square):

| |

Since this was intended only as a prototype, I chose to directly access the tile images from the ZD map repository on GitHub. I would make a copy and serve them myself for a real application, but it was very convenient to use somebody else’s GitHub repository as a tile source while prototyping.

The basic interactive map as displayed in my notebook, using tiles from Zelda Dungeon and capable of displaying any of the three layers.

Coordinate transformations

In order to plot points on the unadorned map that I was now able to display, I also needed to figure out how to translate from game coordinates (from around -5000 to 5000 on both axes) to map coordinates. Mapping tools like Leaflet are usually used to display maps of the Earth or at least other spherical bodies and consequently usually take coordinates as pairs of latitude and longitude, but the game world is much simpler because it’s a flat4 rectangle.

This kind of application is not unheard of however, so Leaflet provides a Simple coordinate

reference system

(CRS) that doesn’t do any of the clever spherical geometry required for

handling maps of the Earth exemplified by CRSes like WGS 84 and

instead one unit on either axis is mapped to one pixel at zoom

level zero. This means that the coordinates on the map I’ve created are from 0 to 564 on both

axes.

Although I could have located some points in the game with known coordinates and manually found their corresponding image coordinates on the map tiles, that would have been somewhat tedious and error-prone work. I instead looked at the Zelda Dungeon map application’s source code again and found that (after some computations) the transformation from game coordinates to tile coordinates (recalling that tiles are 564 pixels square) is best done by multiplying the game coordinate by 0.046875 and adding 282. Of if you like math notation, the following function $M(p)$ converts a game coordinate $p$ to a map coordinate $M(p)$:

$$ M(p) = \frac{564}{2} + \left( \frac{564}{12032} \times p\right) $$

The magic number 564 is the base tile size, and 12032 is a scale factor defined by the total size of the tiles in relation to the game coordinates. Any application using different tiles might have a different CRS, but it’s nice that I was able to reuse the ZD CRS alongside the map tiles.

I wrote a little bit more code to do this coordinate transformation:

| |

..and then to test the transformation, I plotted from the beginning of my save’s Hero’s Path until the first time I teleported.

| |

I knew that I had spent time circling the Great Sky Island during the tutorial sections of the game, so that this track follows logical borders in that area is an encouraging sign that the CRS is correct.

The first couple attempts at this didn’t have a correct CRS; it was either shifted from the correct

location (in a few instances far outside the actual map bounds),

flipped or rotated. I experimented by switching the x and y coordinate orders in a few

places (Leaflet takes Y coordinates first by convention5) and changing the sign of some of

the factors (scale, offset) until I ended up with the above code and image which looks correct.

Plotting deaths and life

That made for all the information and code I needed to make use of footprint data, so as another experiment I plotted every location I died on the map.

| |

It’s fairly clear for looking at this map that my deaths tended to be clustered, rather than scattered; I must have a tendency to treat a death in the game as a challenge and try again until I find a winning strategy, rather than avoiding the area in the name of safety.

This plot is somewhat misleading however because it always displays every point, regardless of which layer is shown behind them. It would certainly be possible to automatically show only the points corresponding to the visible layer, but it may not be possible with ipyleaflet.

I also had a go at drawing the same kind of line that the game displays for the Hero’s Path. As with deaths, this displays activity on every layer in the same way so it’s not possible to tell which layer of the world I was on at any given point; that would be a worthwhile improvement that I haven’t tried to make.

| |

Even with no indication of which layer a given point is on, this track provides a decent sense of where I spent more or less time and illustrates how geography guides the way players move through the world.

This proved that I could do what I originally wanted to do, and it’s where I’m leaving this write-up.

Conclusions

I was somewhat surprised by how easy it was to learn the aspects of the footprint.sav file

format that I cared about, though it was significantly simplified by the existence of documentation

for BOTW’s similar data. I hope my notes on the process are useful even to people who aren’t

interested in the Hero’s Path in particular, since it seems like when others do this kind of

work they tend to only share the results and nothing of the process. The result in those cases

tends to be that the process of reverse-engineering seems impossibly difficult to a beginner,

but I hope that the description of my process (which I developed in an ad-hoc way, never having

tried to do this kind of thing before) lifts the veil on at least one way to approach

this kind of challenge.

In documenting this format I’ve filled in a knowledge gap that at least one other person wanted to fill, and hopefully have enabled others to do interesting things with the data in the future. Although I would like to create some tooling that allows others to visualize their own data with ease, I found that the appeal of doing so had been lost after I prototyped enough to show that it was possible. Perhaps I’ll revisit that tooling in the future, but right now I’m more interested in doing other things.

Since it might be interesting to view, I’m sharing the Jupyter notebook that I was working in when doing the work described in this post. It’s formatted differently from the narrative version here and is probably harder to read, but does offer interactive maps and complete code: TOTK Save Investigation.ipynb.

Extended ideas

It would be neat to visualize where real players have died most often by collecting a bunch of saves and generating a heatmap- I recall the time somebody with access to player data for Just Cause 2 mapped 11 million player deaths with interesting results, and although the Hero’s Path doesn’t permit quite the same level of detail I believe the results could be interesting.

It seems like Nintendo’s development teams have found that it’s nice to capture moments automatically for the player, since this year’s Super Mario Bros. Wonder automatically captures screenshots of gameplay that seem like they have similar attraction. ↩︎

“Hatago” is a Japanese word referring to inns located along national highways in the Edo period, so it makes sense that this word would be used by the developers to refer to the game’s stables that function as a kind of inn. ↩︎

For readers unfamiliar with how map-viewing applications are often implemented, they tend to provide “tiles” (pictures) of map imagery on demand, each of which is fairly small (often 256 pixels square) and has an associated “zoom level”; at any given zoom level a tile can be retrieved that covers any chosen point on the map. This approach is in part a concession to efficiency because a large map represented as a single huge image would often be too large for anybody to view with acceptable performance, and it allows lower zoom levels (more zoomed out) to omit small details that might otherwise make a map difficult to read while still making them visible at higher zoom levels. ↩︎

“Flat” meaning it’s a rectangle that exists in a purely two-dimensional space rather than being projected onto the surface of a sphere (or a shape that approximates a sphere), as real-world maps typically are. ↩︎

Mapping software generally doesn’t agree on whether

(x,y)or(latitude,longitude)pairs are the more correct way to express coordinates. Humans looking at maps usually talk about positions with latitude and longitude in that order, but computer graphics usually uses Cartesian(x,y)coordinates instead (and even then with no particular consistency about whether Y=0 is at the top or bottom of the screen). There’s no sensible way to split that difference, so different libraries often make different choices about the order in which X and Y coordinates need to be given. ↩︎